I’ve written before in these pages about how it came to be that the iconic Dr Feelgood guitarist, Wilko Johnson sparked a second career for me in music photography. In essence, it was his terminal pancreatic cancer diagnosis in late 2012 and the (apparent) sure knowledge that I wouldn’t ever see him play again beyond his ‘farewell’ tour in early 2013 that made me want to document live music. I was a huge fan. I’d seen Wilko play many, many times, but had no permanent, tangible memories. The theory in my head was that if an artist I loved could be so cruelly taken away from me like this, then who might be next? I suddenly wanted those permanent, tangible memories.

Of course, to think like this was an act of extreme self-indulgence. Wilko was obviously the person who mattered here. So, when it came to pass that his initial diagnosis was wide of the mark and through the expertise of cancer specialist Charlie Chan and surgeon Emmanuel Huget, he was given a second chance at life, I’m pleased to report that my first thought was to be delighted for him. But I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that my second thought, which arrived not long after, was that maybe I might get to photograph Wilko after all…

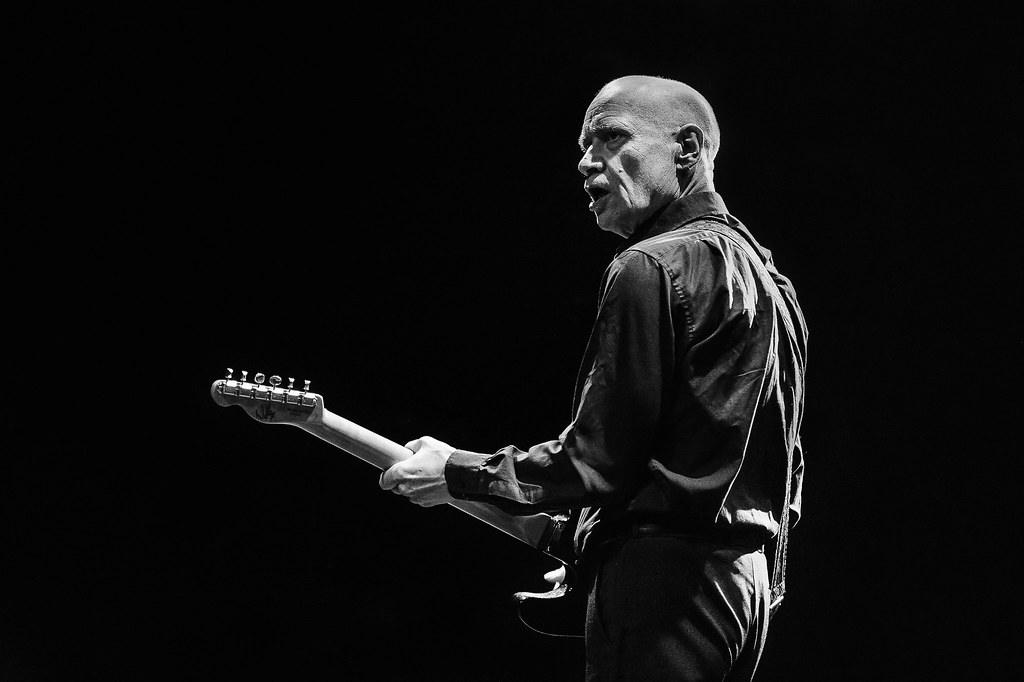

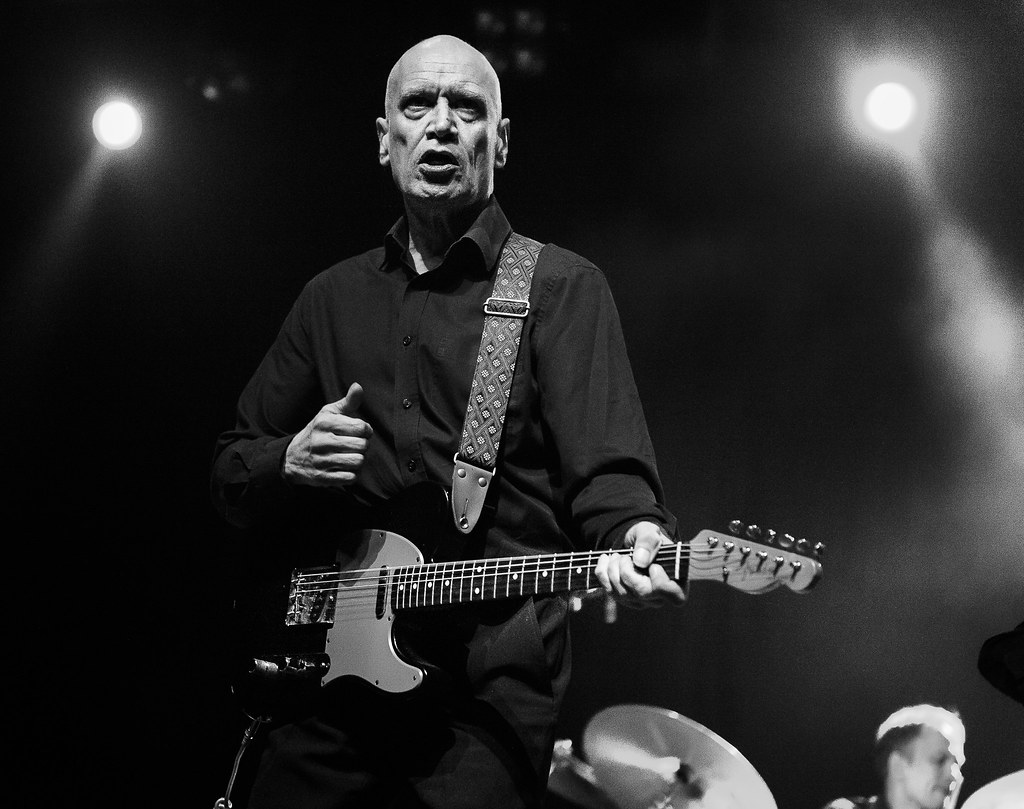

In the end, I did get to photograph him after all; quite a number of times in fact. Each one of those times felt like a precious gift; opportunities I certainly didn’t expect to receive. I’m really pleased to be able to say that I never took an evening in Wilko Johnson’s company for granted ever again. And I’m glad. It was announced this week that Wilko passed away at home on Monday evening. The outpouring of emotion I’ve seen in both the mainstream and in social media in the last few days has been really moving and it’s comforting to realise just how much Wilko clearly meant to so many people. All of a sudden, those photographs I didn’t expect to take, mean a great deal more. So, I’d like to share some.

My first opportunity to photograph Wilko came in December 2014. I was actually at a Blockheads (as in, Ian Dury and the) gig at The Jazz Café in Camden. They had a habit of doing a Christmas show there and by now I was establishing a habit of snapping it. Wilko has a strong connection with the band. He held a brief position in it from 1980, where he made the acquaintance of ace bassist Norman Watt Roy. Norman has been stage left to Wilko’s stage right ever since.

Given those connections, there were rumours circulating in the venue that Wilko might be there but even so, when he appeared at the end for a couple of encores, I really couldn’t believe it. It was only a few months after his surgery and whilst he was obviously still quite frail, it was the best Christmas present I received that year for sure. And just in case you’re wondering why he’s not with his signature black Telecaster with the red scratch plate; he’s playing Chas Jankel’s Tele instead.

Wilko’s first ‘real’ return to the stage came the following spring at the Shepherds Bush Empire. He was in fine form, skittering left and right, much as he had before his enforced layoff. In fact, it’s safe to say he was more upright than the letters which formed his name outside.

The empire is a lovely venue and a great place to take photographs. The stage is extremely low so at the very front you feel practically on top of the talent. Sadly, at the very back, you can see virtually nothing at all, so always best to get there early.

In 2009, Julien Temple made a film about Dr Feelgood entitled Oil City Confidential. It was superb; one of the best ‘rockumentaries’ ever committed to tape and Wilko’s extraordinary personality shone bright. Neither Temple, nor Johnson could have known then that there would be a sequel. In 2015, Temple made The Ecstasy Of Wilko Johnson. Filmed during Wilko’s cancer journey, it documented Johnson’s feelings around expecting to die and being offered a chance to live. It’s another remarkable piece of film making.

I attended the premiere at Picturehouse Central, just off Shaftsbury Avenue. Wilko is with Norman Watt Roy, Julien Temple and his drummer Dylan Howe.

After the premiere, we made our way through Soho to the famous 100 Club, where Wilko and the band played an extremely intimate gig. The opportunities to shoot very close, very wide-angle photos were rife.

My next appointment with Wilko was the following spring at The Forum in Kentish Town. It doesn’t have the ambience of Shepherds Bush and certainly doesn’t have the intimacy of the 100 Club. But it did have decent lighting with oodles of contrast, which made for nice images.

One from this set of photographs made it onto Wilko’s tour merchandise. It would have been a nice payday had I resisted the temptation to buy half the inventory for family and friends.

Wilko released an autobiography in the summer of 2016. It was entitled Don’t You Leave Me Here and it’s a great read. The book was launched at Rough Trade East where Wilko read some passages and he was interviewed by long-time friend, wife of Dylan, and all-round good person Zoë Howe. It was an opportunity for me to shoot some quick portraits. They’re some of my favourite images.

My next grab of Wilko in pixels came the following year. 2017 was special as it marked the 30th anniversary of his band and the 70th anniversary of his time on earth. So, it needed a special gig, and it got one; a sell out at the Royal Albert Hall. I managed to get on the photo list, which was a privilege for such a venue – but it was a difficult shoot. Stood in a stairwell with no opportunity to move and no other angle but the one we were given. Still, you do what you can with what you’ve got.

2018 saw another release, this time of a new studio album, Blow Your Mind. There was a signing at HMV Oxford Street and I was there for a few pictures. This was the second time I’d had the pleasure of seeing Wilko in a relaxed setting with fans and the warmth in the room clearly flowed both ways. There are so many pictures of him with wide open eyes and a menacing stare. When he broke character, the smile was as wide as the eyes were bright. The whole band were tremendous fun that afternoon.

By now, I’d managed to photograph my inspiration plenty of times and whilst every encounter was special, it was great to have a particularly noteworthy reason to do it again. One presented itself in March 2019 when Wilko played the Cliffs Pavilion, Southend, a theatre around ¼ mile from his house. Wilko and Dr Feelgood sit at the very top of a rich lineage of RnB music that hail from this part of Essex. Will Birch, The Hamsters, The Kursaal Flyers, Mickey Jupp, Eddie & The Hot Rods. You get the idea. All have emanated from here.

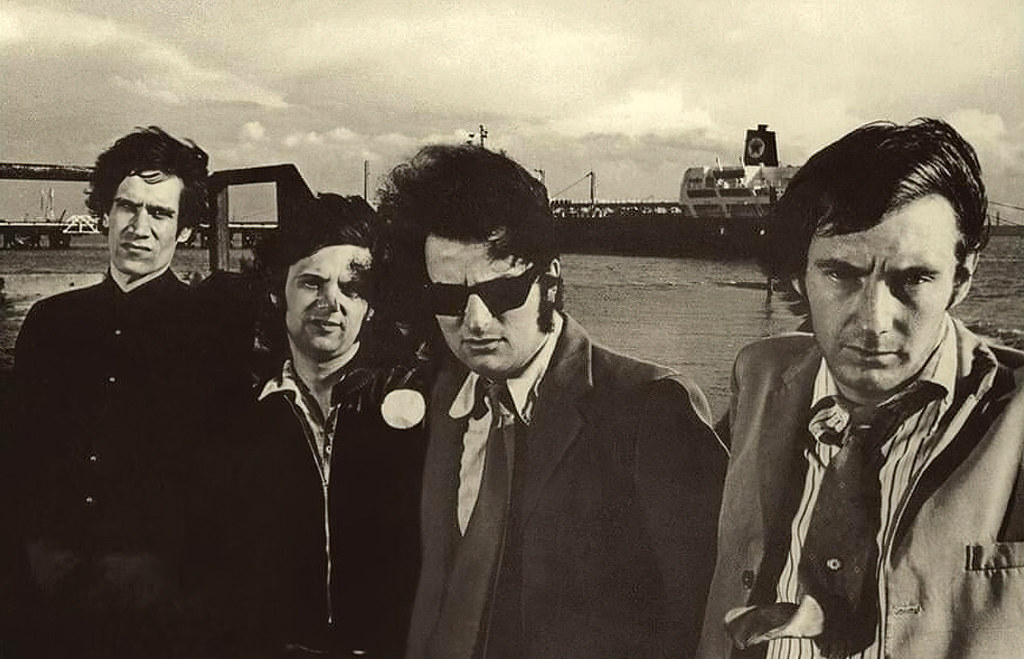

The members of Dr Feelgood were raised on Canvey Island, just down the road. Canvey comprises seven square miles of reclaimed mud flats in the Thames Estuary and it somehow conspires to have several hectares that exist below sea level. A sea wall protects it from high tides and as a result you can’t see the estuary from within. In the 60s and 70s, the western end of the island was dedicated to the petrochemical industry and Coryton Refinery is just over the creek. These days, Canvey hosts a graveyard of disused oil tanks. It’s a weird place and one I wanted to check out before the gig in Southend.

Some parts are immortalised in Dr Feelgood folklore. The cover shot on the debut album Down By The Jetty is taken on the sea wall outside The Lobster Smack pub.

I took a version of it. It’s essentially the same as the original; if you can accept my version is in colour and is missing the band and the ship docked on the jetty.

The Labworth restaurant which also looks out over the estuary was built in 1933 and is Grade II listed. It was designed by the distinguished engineer Ove Arup to resemble the bridge of the Queen Mary. I’ve no idea who painted the ‘Canvey is Englands Lourdes’ mural on the sea wall, but both were heavily featured in Oil City Confidential so I made sure I tracked them down.

The gig itself was good, Wilko and the band in great form as ever. The Cliffs Pavilion is a large municipal theatre and the audience was all seated. I freely accept that Wilko’s core demographic (and I’m squarely in it) are of an age, where sitting at the gig is probably deemed most appropriate; but in my humble opinion, to be seated at a Wilko gig was the very definition of a missed opportunity. I certainly can’t comfortably sit down in front of any rhythm section which has Norman Watt Roy in it. It’s just not natural.

The enforced Covid layoff meant that my next, and sadly last, meeting of the camera and the Wilko Johnson Band came in February of this year. He was doing a tour with the irresistibly entertaining John Otway. It was another theatre, though the theatre in question was the very splendid New Theatre Royal in Portsmouth. Being a seated theatre show meant another long lens and pictures from the side of the auditorium, though I was able to steal a few from the back later on.

So, the moment I’d feared nine years ago has finally come to pass and I feel desperately, desperately sad; but I cannot express how grateful I am to have had those extra years to watch Wilko and the band play. I also cannot express how grateful I am to Wilko, not only for all the gigs through the years and the immense enjoyment he gave me as a witness to those performances, but also for the gift of the mid-life crisis that is my photography.

I feel too of course for Wilko’s family, for all the other fans of the man who must be feeling like me, and also for the small number of people I’ve got to know through taking Wilko’s photograph who have a far closer relationship to him than I ever did. I’m thinking of you all.

Wilko, you were one of a kind. There was nobody else like you, there was nobody that matched you, there will be nobody who follows you. Thank you for everything.

Wilko Johnson: 1947 – 2022

Wilko Johnson’s website is here. Wilko can be found on Facebook and Twitter.

Memories and photos of Wilko Johnson by Simon Reed.

Simon Reed is a freelance music photographer and writer based in the Surrey Hills around an hour from London. His personal website Musical Pictures is here. He is also on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

Share Thing